I really did not want to write two consecutive posts about albatrosses,

but the situation just plain demands it. Let me explain. As I discussed in my

previous post, the process of raising a young albatross is very

time-consuming and complicated and demands incredible endurance on the part of

its parents. I didn't say too much though about how arduous the process is from the point

of view of the young chick but given what’s going on around here on Midway right

now, I feel compelled to share some of my thoughts and observations about it.

As is the case for all birds, the life of a chick begins

while it’s in the egg. For a Laysan albatross, this lasts about two months while parents take turns incubating it. After

spending a couple of days pecking its way through the shell, the newborn hatchling is

wide-eyed but small (less than half a pound) and very vulnerable and is thus

brooded and guarded by its parents who ensure that a frigatebird or other avian

predator doesn’t fly off with it in its beak. Next is a prolonged period of rapid growth with occasional feedings by

the parents who travel far into the ocean to procure food for the ravenous

chick. This goes on for about five months until the chick is ready to move on

to its next stage of life for which it must learn to how fly and forage on its own, completely

independent of its parents. As Laysan

albatross begin nesting around the first of the year, early July is an

especially important and exciting time and Independence Day (the rarely invoked but official name of the Fourth

of July holiday) takes on real significance.

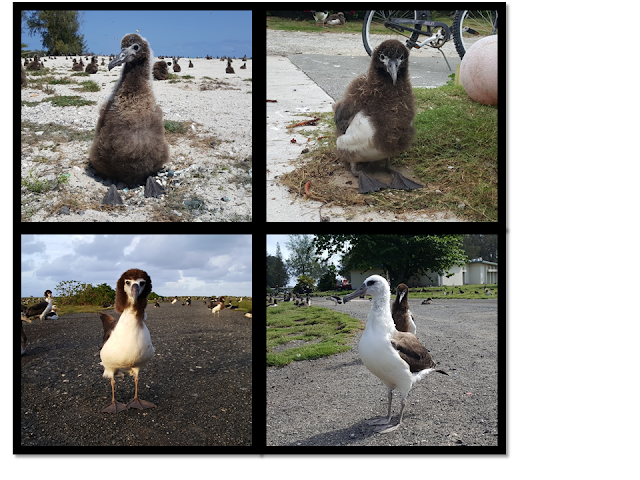

When I arrived on Midway back in mid-April, the chicks were about two months old, downy and plump. Over time, I began to see signs that some were growing adult feathers, usually just a stripe of white visible on the wing from deep below the down. Eventually smooth wing feathers began to develop and the down gradually began to disappear. I remember one day a few weeks back riding my bike to work and doing a double take after I saw a chick wearing a suit of feathers that looked almost exactly like that of an adult.

Then something really

startling happened. Chicks began flapping their wings! Rainstorms seemed to really stimulate this

behavior, perhaps because it helped them keep their feathers dry. It wasn’t

long before some of the older birds began catching air on days when the wind

gusts provided them with sufficient lift (the design of an albatross’ wing

makes it difficult for even adult birds to take off using just the power of their

muscles). Once a young bird feels the thrill of flight, it figures out that it

can accomplish even more with a running start. And so it’s been for the past month or so with birds making incremental

progress day by day with some leaps and bounds on the windier days.

|

| A young Laysan albatross catches some air during a squall on Sand Island, Midway Atoll. |

In the past week though, something even more remarkable has

been taking place. Some young birds are

feeling confident (or desperate) enough to leave their nest sites and making

their way towards the shore. This is a

sure sign that their parents are no longer delivering food for them as parents

recognize their young not by who they are but by where they are and once a chick wanders more

than a dozen feet from its original nest location, adults can't find them. Many chicks seem curious about the water and venture

out to swim. Some have been seen making short flights across the open ocean but many

more though have washed up dead on the beach or in the harbor.

|

| Many Laysan and a few Black-footed albatross have left their nest sites and converged on Turtle Beach, Midway Atoll. |

It’s a very tense time here on the atoll as young albatross strive

to make it on their own. While it seems like just yesterday the island was busy

with dancing young “single” albatross and parents were frequently seen coming

and going to feed their offspring, now the chicks outnumber adults about fifty

to one, and it is rare to see a chick being fed. When an adult does show up

there’s usually a period of five minutes or more of confusion as it is

surrounded by hungry peeping chicks and it must figure out which mouth among

the many is its actual offspring. Some chicks still look so downy and small

that it’s hard to imagine it will be able to make it and one broiler of a day

could put a lot of them over the thermodynamic edge.

The tension rubs off on me

too and I find myself feeling anxious about the fate of all of these birds and can’t help but

feel some despair when I find yet another one dead on the road, on the beach,

or in my backyard. The best way I've found to keep it from getting me down is to simply try to keep my focus on the birds that seem to be doing well and encouraging them on in my

own way. (I also have been known to try to rescue drowning albatross and have a bite mark on my left arm as a result!).

|

| One fledgling Laysan albatross takes a short flight while another dries its wings in the inner harbor of Sand Island, Midway Atoll. |

It's been an intense and interesting weekend and I've spent a lot of it watching the albatross and thinking about the amazing lives they lead and how for many animals the chances of making it from newborn to independent adulthood are pretty slim. In a weird way it's made me appreciate my own life even more and made this Independence Day an especially meaningful one.

Rob, I loved this piece, and it reminds all of us that survival (for any creature) is not a given. I can absolutely see you trying to rescue a drowning albatross! You are still such a kind and passionate person!

ReplyDelete