Why

wildlife at Midway Atoll aren’t afraid of people and what that does to you

One of the great mysteries of modern biology is how it is

that Charles Darwin knew so damn much. Not only did he correctly explain the mechanism

by which the diversity of life on earth was created (i.e., the Theory of

Evolution by Natural Selection) but as if this was not enough Darwin applied

his genius to a variety of other subjects including the domestication of pigeons, earthworm

biology, and the geology of islands. One of the first stops made by the HMS Beagle made

on its voyage to explore South America was the Galapagos Islands where Darwin noticed

something very strange about the wildlife there. They weren’t afraid of people.

Darwin had an explanation for this, of course. On remote islands where mammalian

predators were absent for thousands of years, there was no advantage for an animal to flee when approached

by one. And if there was no advantage, maintaining that behavior would be a

liability over evolutionary time. It all comes down to this: maintaining any unnecessary feature – anatomical

or otherwise – constitutes a cost to an individual which over time results in

lower fitness compared to an individual possessing only the things it needs to

survive in its environment.

Had the Beagle sailed for the remote Northwestern Hawaiian

Islands instead of the Galapagos, Darwin probably would have still come to

the same conclusion. Like the Galapagos, these remote islands were never

inhabited by people until very recent times and the native wildlife –

predominantly birds – evolved with no predators. The lack of fear that the

birds of Midway have for people explains why shipwrecked sailors in the 18th

and 19th century and early feather hunters had such devastating

effects on them. When approached the birds did not flee so anyone wishing to capture them for either the stewpot or the cargo hold could do so

with little effort. Tens of thousands of birds were taken as a result and the populations

of albatrosses, terns, shearwaters, and other species plummeted until regulations were affected by US President Teddy Roosevelt during the first decade of the

twentieth century.

|

| A Laysan Albatross hangs out on the sidewalk in front of the Midway Gymnasium. |

As populations began to recover, people began finding

reasons to inhabit these remote islands. The first were personnel hired by the Pacific

Commercial Cable Company to build and operate a telegraph station established on Sand Island of Midway Atoll in 1904. Employees – mostly from the

mainland US – found themselves living among millions of seabirds that seemed to

take little notice of them which certainly must have been perplexing. Despite decades of persecution, the birds still did not fear people. (Darwin would

likely have an explanation for that too!) Laysan albatrosses, the most numerous

birds on the island, built nests out in the open making little effort to

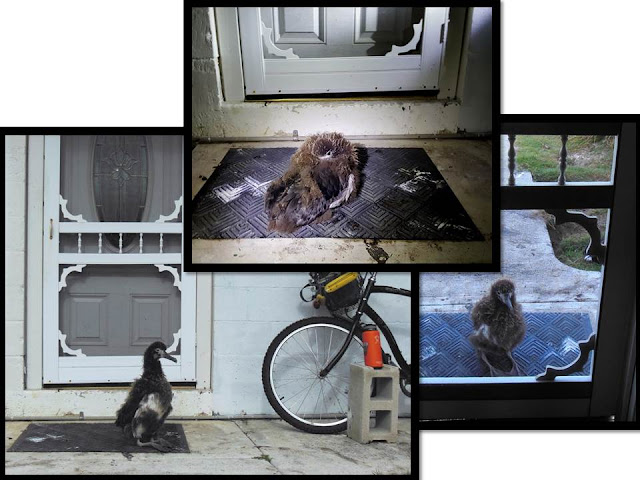

conceal them, left their young unattended on the front porches of houses, and conducted

their elaborate courtship rituals in close proximity to anyone who happened to

pass by. Other species – terns, noddies, tropicbirds, etc. – behaved in similar

fashion. Maybe, by living in such close proximity to such magnificent creatures,

it was inevitable that these early residents of Midway developed a genuine

respect and deep appreciation for their avian neighbors. Early records attest

to this in various ways: from the decision to ban cats and dogs from the island

to the formation of the Goofy Gooney’s

Club which honored "the silent cooperation given them by the curious residents

of the Midway atoll to the new strangers and the hazards they brought”.

It wasn't long before the Midway and other Northwestern

Hawaiian Islands were recognized for their potential strategic military importance.

But even as Midway was transformed from a sleepy telegraph station to a prominent

Naval Air Facility, amicable relations between the seabirds and the human

inhabitants persisted. This is not to say that there wasn't an

impact on the birds; habitat was destroyed, antennas, seawalls, and other

hazards to birds were erected, and many seabirds were undoubtedly killed through

collisions with aircraft and other causes. Some species, such as the Laysan

Rail, were not able to cope with the change and went extinct but most were able to adapt. Through it all, the people of Midway seemed to take a certain pride and interest in the birds. The official

insignia of Midway – an image of two Laysan albatross “sky mooing” – eventually

embellished everything from a the island newspaper to the movie theater.

Today, the folks living on Midway continue the

tradition of tolerance and respect for their avian neighbors. People dodge

albatrosses every day while travelling to and from work and pick up chicks off

the road when necessary. When the sun sets, windows covered with curtains or blinds in religious fashion lest Bonin petrels, nocturnal seabirds attracted to light, fly into them. In the morning White Terns perch on the windowsill and stare at you through the window. Tropicbirds brood their chicks in the front yard in full view and emit a harsh bark only if you get so close as to risk stepping on them. Laysan’s ducks forage on the patio and parade their chicks through the yard. And people still pay homage. The electrician’s golf cart has an

image of an albatross painted on its side and at a recent evening of karaoke seabirds were displayed along with the lyrics to the songs.

After being here for about a month and a half, I still can’t

fully wrap my brain around how living so closely to all of these birds affects me. Certainly, I feel a connection to them and affection for them. But it goes beyond that as well. There's something about living in a place where the hustle and bustle isn't about selling something or taking care of people's needs. to be in a place where birds are truly at center stage has a strange effect on a person. I'm not sure I can say much more that that for now, maybe I will elaborate in a future post. In the meantime, I’ll continue to say “good

morning” to the albatrosses outside my front door, beg forgiveness when I

pass too close to a tropicbird’s nest, and continue to learn more about these fascinating animals through these close encounters.