Miscellaneous notes on the ontogeny of Laysan Albatross

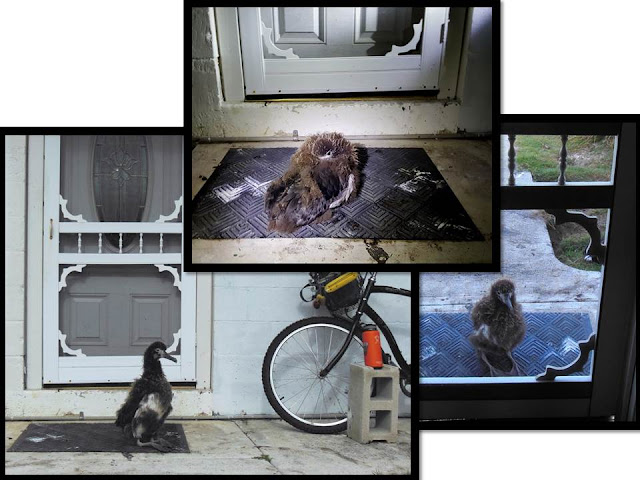

Prior to my arrival on Midway Atoll, a Laysan Albatross decided to lay an egg on the welcome mat outside of the front door of the house that I’m currently living in. The egg hatched sometime in late January or early February and the chick is now fairly large (6 or 7 lbs) but still not very mobile and still spends a lot of its time either on the doormat or within a few feet it. If I were the naming kind of guy and knew that said chick was a male, I might bestow the name “Matthew” (long form of “Mat”) to this chick but since I’m not and I don’t, let’s just stick with calling it “the chick” for now.

|

| A Laysan's Albatross chick lives just outside my front door |

The growth and development of an albatross chick is a very

long process; it takes on average 165 days for a chick to fledge after hatching. During

that time, the parents – both male and female – fly long distances out into the open ocean to

forage for food for the youngster returning once every few days or so with a

belly full of partially-digested food that it then regurgitates to provision its

offspring. Squid, fish eggs, fish, and crustaceans comprise the bulk of the

Laysan Albatross diet and, unfortunately, plastic debris ends up being eaten as

well as fish and crabs sometimes lay their eggs on these floating objects.

All of this ends up being fed to the chick as well which lead to a problem.

Some of this material – including the squid’s beaks, lenses of fish eyeballs,

pumice, and plastic – is indigestible and builds up in the chick’s stomach.

|

| The amount of effort required by Laysan Albatross parents to raise a chick is extraordinary. For nearly six months, both parents travel far into the ocean to gather food for their chicks. |

The other morning as I was leaving my house to go to work, I

found an interesting mess on the welcome mat outside the front door. The chick that lives there apparently had

regurgitated its very first bolus! An essential part of chick development is the regurgitation of a bolus of undigested material. Although it was messy and somewhat gross (though many of the boli I've seen are fairly compact, my neighbor seemed to take more of a "shotgun approach"). I realized that this was a good thing! Why? Because the buildup of all of this stuff in the chick’s gut inhibits its ability to take in new food and also adds to its weight making it more difficult for it to lift off during its critical first flight. So as you can imagine I was pretty stoked for the chick because even though I refuse to name it, I still admit to having developed some affection for her/him and I like to think that the feelings might even be mutual (the chick no longer snaps its bill at me when I enter or exit the house and we seem to have a friendly relationship of sorts).

The accumulation of plastic in a chick’s stomach is, of

course, a worrisome phenomenon. In fact, some chicks get so filled with plastic

that they are unable to feed or suffer internal injuries from sharp fragments. Sometimes this even results in them dying from complications. Plastic and other debris that

accumulate in the ocean is an hugely important topic and one that I plan on addressing in a future post but if should you want learn more about this very

important issue now, check out the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administrations webpage here.

At about four or five months out, the albatross chicks are at an interesting stage of development. It seems like a lot of chicks are “throwing” their first bolus as new ones appear every day on the roads and paths that I travel. Nearly all chicks are also showing some signs of molting into their adult feathers with most seeming to be stuck in an “awkward stage” though some have pretty impressive suits of feathers. Although still very attached to their nest sites, many chicks are now able to stand tall on their legs and even stroll around a bit. They also seem anxious to flap their ever growing wings, especially during strong winds or bouts of rain.

Given how many albatross chicks are around here (literally

hundreds of thousands), it’s hard not to pay attention to them and to

appreciate the progress they show in their continued growth and development. Besides, what else are you

going to do on the weekends here at Midway Atoll?

Touching!

ReplyDeleteThis is so cool, and i'm learning so much, mostly about how detrimental plastic in our environment is. I'm more motivated than ever to stop using plastic bags and keep plastic out of the ocean

ReplyDeleteReally glad you are getting so much out of it. Dissection of albatross boli are used in many schools across the country to bring awareness to the enormous problem of marine pollution. Check out this from National Geographic.

Deletehttp://nationalgeographic.org/activity/laysan-albatross-virtual-bolus-dissection/

I should've waited until after breakfast to read this one...

ReplyDeleteLove the description, RVT

ReplyDeleteThanks Lindsey!

DeleteNot the naming kind of guy? WTF, mate?? I recall a certain predilection for applying monikers to just about anything. Remember Melagris?

ReplyDeleteGood point Lafite. I guess I more inclined to name a GPS unit or a storage box than I am a wild animal though. I never even gave names to the squirrels in the backyard in Enterprise. This is interesting stuff that maybe I would need a therapist to untangle. Unfortunately, there aren't any within a 1000 miles of here.

DeleteCheck out this link to read a story about albatross chicks and the plastic issue

ReplyDeletehttp://www.fws.gov/news/blog/index.cfm/2012/10/24/Discarded-plastics-distress-albatross-chicks

Fascinating! Thanks for sharing this. I'd consider it an honor if an albatross laid an egg at my door and I had the pleasure of watching the chick grow. Of course, it could get messy after a while! Maybe you could put down some of those puppy house-breaking pads on the porch? ;)

ReplyDelete